How Demand and Supply Determine the Price of a Good

The mass is compiled of millions of individual parts: prices, producers, purchasers, payers of rates and taxes, etc. In this chapter, we shall break up the mass into individual components and conduct a detailed survey of suppliers, consumers, firms, and industries. For better understanding avail the help of an economics homework help expert. Underlying all our economic analysis will be the fundamental fact that economics is concerned mainly with prices; economics is also the study of scarcity, and this means that individuals must exercise choice; the selection and allocation of scarce things are conducted through the price mechanism. From the beginning of economic studies, men have been preoccupied with the forces that determine the price. Thomas Aquinas and the schoolmen contemplated what was a just price'. However, there is no such thing as a "just" or "right" price. "Economics is not concerned with the moral or the right' in an ethical sense."

The potato is socially more essential than the pineapple. This would explain the difference in price in favour of the pineapple. The herring is socially more important here than caviar, is probably more nutritious, and therefore more commendable. Account for the price differential here, and then account for the fact that where the pineapple is grown and the sturgeon harvested, the stuff is cheap and no doubt socially despised. (George Schwartz, The Sunday Times Business News, 25 October 1970.)

In a free enterprise or market economy, differences in prices can only be explained by reference to supply and demand as the governing economic forces.

A study of the evolution of economic doctrine reveals that the development of the idea that the forces of supply and demand were at the root of all price differentials took three main stages.

- Early emphasis was placed upon the supply side According to classical economists, the cost of labour was the main determinant of price. Adam Smith argued that the price of an article depended upon the labour expended in its production; if an employer had to employ twice as many workers, or if the workers had to work twice as hard, then it appeared obvious that the price of the article would be twice as much. 'Labour is the foundation of all value,' argued David Ricardo. However, there are some obvious difficulties, illogicality's, and paradoxes in the labour theory of price determination. For example:

- Waste of labour. Despite the excellence of the workers if there is no demand for an article, it will not command a price.

- Difficult to measure the effectiveness of labour. Some men are more efficient or work harder than others.

- Combination of labour with other factors. The productivity of labour depends upon the efficiency of capital and management.

- Importance of labour to society. Is a manager worth more than a manual worker?

- Past labour. Prices of goods already produced are subject to change, e.g., works of art.

- Attention turned to the demand side In the same way as Smith, Ricardo, and Mill oversimplified the problem of price determination by concentrating almost entirely upon the supply side, so Jevons, Menger, and Walras, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, often seemed to suggest that the complete answer could be found from the demand side. After the earlier overemphasis upon the supply factors, these economists made a fundamental contribution to economic thought by correcting the balance and pointing out the importance of demand factors. Stress was now placed upon marginal utility as the key influence on prices.

- The interacting influences of supply and demand brought together and placed in proper perspective Credit for this eclectic feat is often given to Alfred Marshall, who published his Principles of Economics in 1890. Marshall saw that the determination of all prices could not be ascribed to either supply, on the one hand, or demand, on the other. He built up a dual theory that some prices were influenced more by the supply side (costs of production), while other prices were largely determined from the demand side (marginal utility). An analogy of a pair of scissors has been used to illustrate the crisscrossing of supply and demand, and indeed this analogy is apt as we shall see when we consider graphs illustrating supply and demand.

The labour theory of value was qualified and extended by John Stuart Mill in Principles of Political Economy (1848). According to Mill, the cost of labour, land, and capital all contributed to the value of an article, but he was unable to explain why goods supplied by different producers (who were subject to very different costs of production), often sold for the same price.

In the long run, the cost of production (supply side) will usually play a more significant part in the price that is charged. J. S. Mill declared that: 'Cost of production would not affect the competitive price if it could have none on supply. If the price of steel rises, this will be reflected eventually in the price of cars. If the supply of herrings is reduced, capital will tend to migrate from the fishing industry and there will be fewer drifters; in the long run, there will be fewer herrings and a higher price. In the short run, demand often influences price-especially the prices of articles that are not the result of mass production by international companies in extensive factories. Weather, taste, fashion, fads, and fancies all play a part in changing demand patterns that will comparatively quickly bring about changes in prices.

The Laws of Demand and Supply

It was suggested from the beginning of this book that the laws of economics should be treated as general trends and tendencies. It will be seen later. for example, that there are at least four exceptions to the Law of Demand, and there may be others that the student can think of for himself.

The Law of Demand

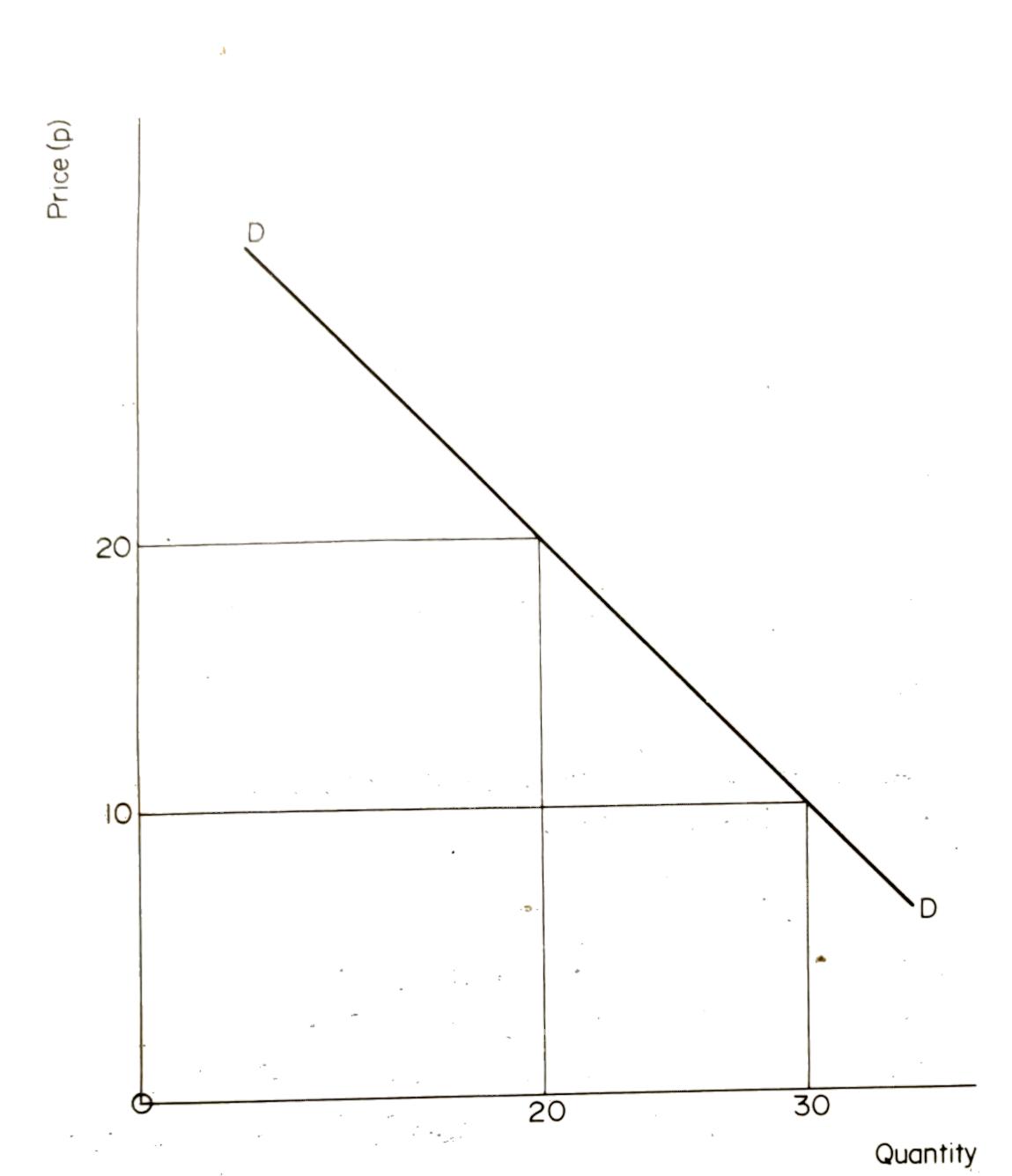

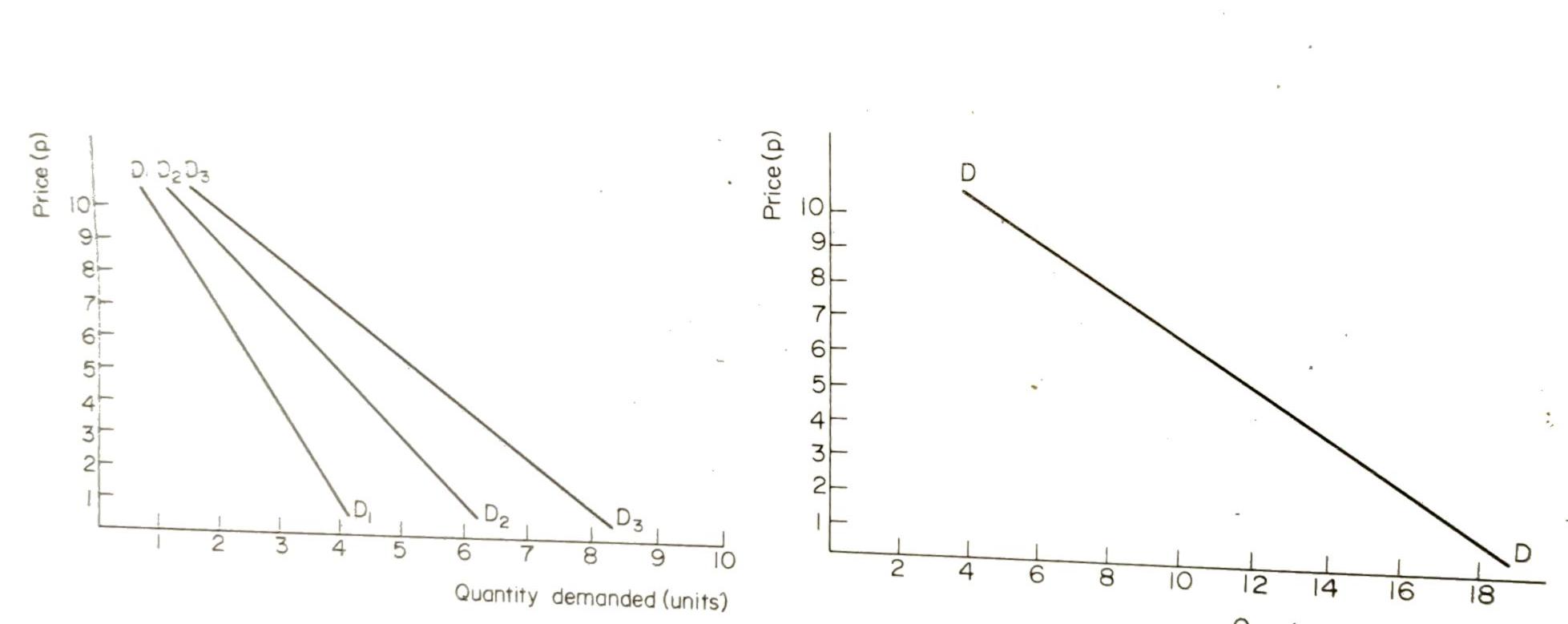

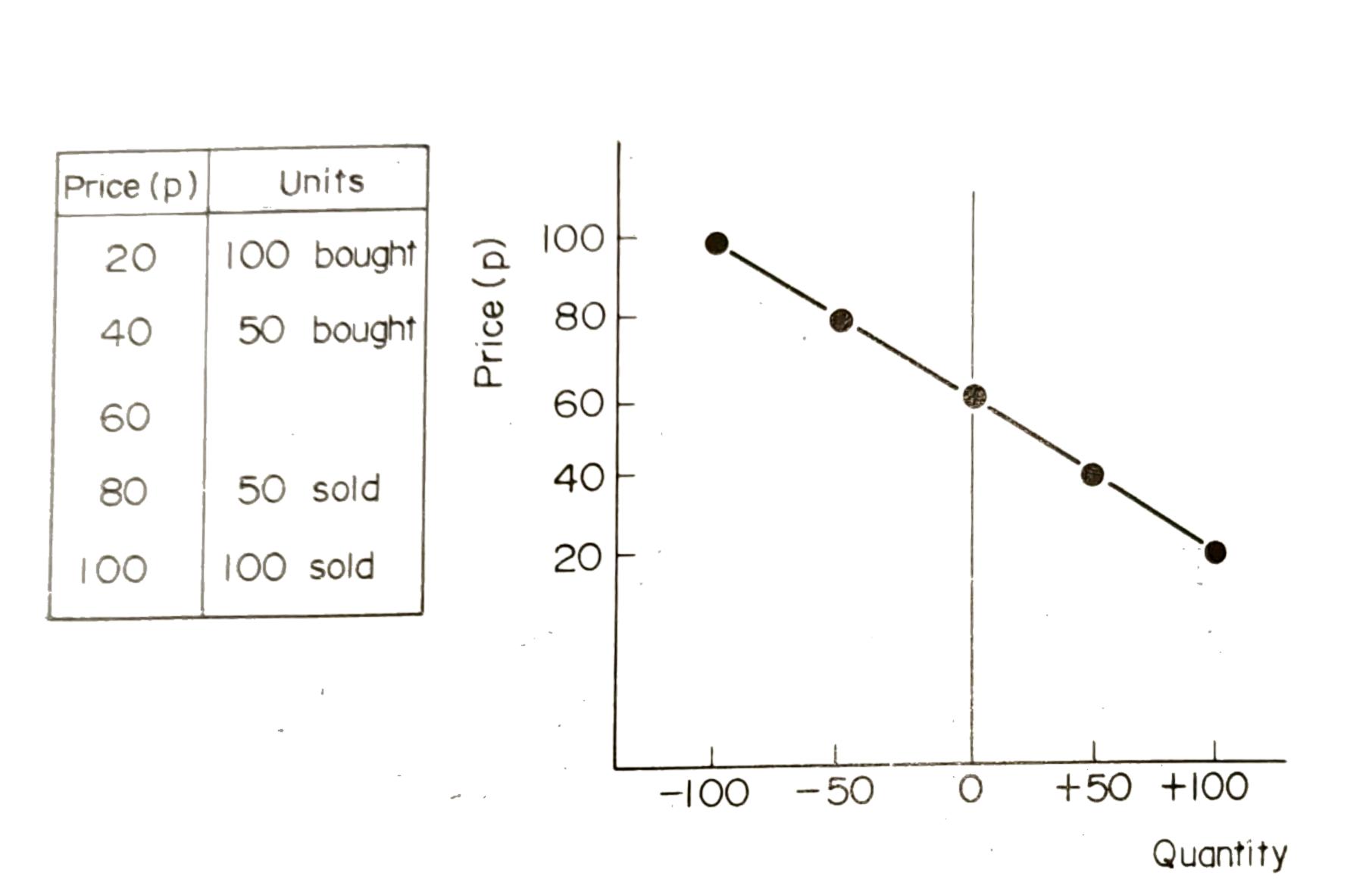

The Law of Demand states that there is an inverse relationship between the price charged and the quantity of the good demanded or in simpler terms if the price rises, less will tend to be bought and if the price falls, more will tend to be consumed. The words 'bought' and 'consumed' have been used here purposely, rather than the word 'demanded", because in economics we are only concerned with effective demand, which means that the person requiring the article must not only be willing. wanting, and waiting to buy, but must also possess the wherewithal to make his demand effective.

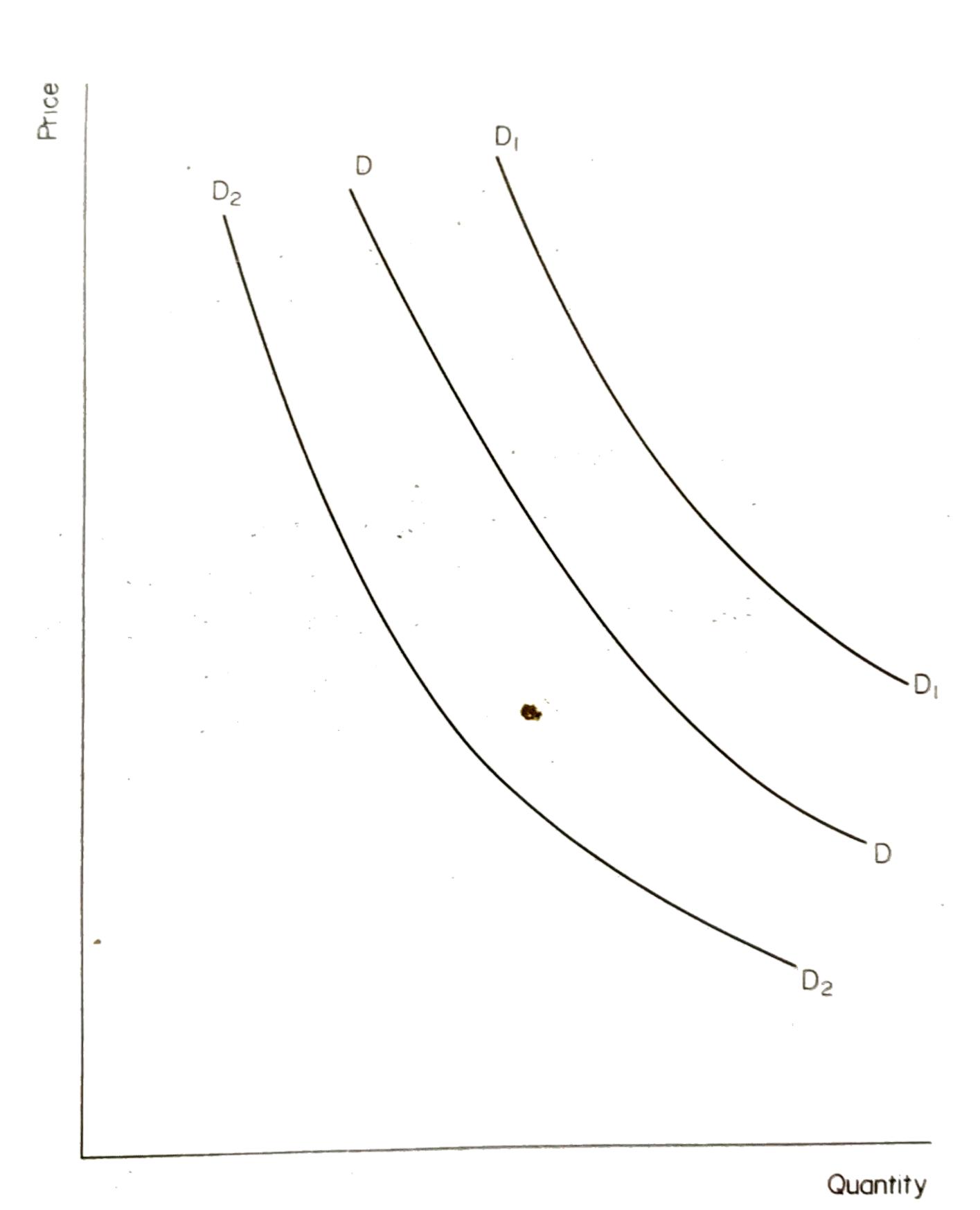

The Law of Demand can be expressed, in three ways: verbally, statistically, and graphically. The demand curve will, therefore, slope down from left to right in normal cases. The main explanation of this elementary empirical law is that each individual has a scale of preferences, and he is always substituting at the margin in an attempt to maximize his satisfaction on a given income: this is sometimes known as the substitution effect, whereby if the price of a certain commodity is increased, then the consumer will tend to substitute a cheaper product. On the other hand, if the price is decreased, there is a tendency for each individual to demand more. Assuming other factors remain static and that only price moves, there will be an extension or contraction of demand. i.e., a movement along the same demand curve.

Exceptions to the Law of Demand

- An affluent society In an affluent society, the demand for inferior goods, such as potatoes or bread, may decline even though the price falls. Following Engel's Law, people on higher incomes will tend to spend a smaller proportion of their income on foodstuffs; this is especially true if one considers a society of overweight, sedentary workers, living in fear of coronaries, and being exhorted to slim for the sake of health and lower life insurance premiums. They may forgo carbohydrates (even if goods in this category have been reduced in price) because they can afford protein foods that may have been increased in price. In this case, consumers' actions are dependent upon an increase in real income, and the concept of income elasticity of demand which we shall study later.

- A subsistence society It was fitting that the possibility of perverse, or upward-sloping demand curves, should have been put forward in nineteenth-century Britain, a century when the Tolpuddle Martyrs received only 8 shillings a week, the poorest paid workers depending upon bread or potatoes as the staple diet. Sir Robert Giffen is usually credited with drawing attention to the fact that poverty-stricken families might conceivably be compelled to purchase more bread if the price of bread was increased. Inferior goods in a subsistence economy have been called 'Giffen goods'. Thus after the 1845 Irish potato famine, the Irish not only spent more money on potatoes but bought larger quantities because they could not afford meat or cheese.

- More and more money might be spent on bread.

- A larger quantity of bread might be purchase.

- A 'status symbol' society Articles of what Professor Nevin has called 'human ostentation' (Economic Analysis, Macmillan) are often desired merely because they are expensive. The higher the price, the more they are demanded. Study this abridged excerpt from Drive, the AA Magazine.

- A speculative society If it is believed that there will be further increases in the price of a good, then consumers may purchase a larger quantity even though the price is rising. This applies especially to speculators on the commodity markets or the Stock Exchange where there is a 'bull market', i.e., a market of rising share prices. While the price was rising, demand was increasing because speculators thought that the price would rise even higher. Judging with hindsight, when would it have been best to have sold out? But speculators are not able to foresee the future accurately so demand may increase in the optimistic assessment of further rises in the share prices. Eventually, it becomes clear that prices are declining over a long period and the demand curve will take on the usual falling to the right position.

Indicating that with an increase in the price of bread, the demand for bread could increase in two ways:

BEFORE

5 loaves at one shilling = 5 shillings Available for other goods = 3 shillings

AFTER

6 loaves at 1s 2d = 7 shillings Available for other goods = 1 shilling

In 1911 the Maharajah of Mysore ordered a custom-built Silver Ghost Rolls-Royce. During the next fifty-three years, it was driven just 7000 careful, stately miles before being bought for about £600 in 1964. Recently, Victor Barclay, the London Rolls-Royce dealer, sold it at auction for £9800. Today this luxury car might well sell better at £30 000 than for a mere £10 000.

During a sale, a well-known store is reputed to have filled a shop window with ladies' hats at 25p each. Only one hat was sold during the morning. Who would buy good millinery at 25p? In the afternoon, the price was 'upped' to £1.50, and the hats were cleared before closing time.

The Law of Supply

The Law of Supply and Demand Equilibrium

- Many buyers and sellers.

- The goods bought and sold are homogeneous.

- No discrimination in the form of favouritism or prejudice between buyers and sellers.

- Close contact between buyers and sellers.

- Relatively easy portability of goods.

- Comparatively simple transferability of goods.

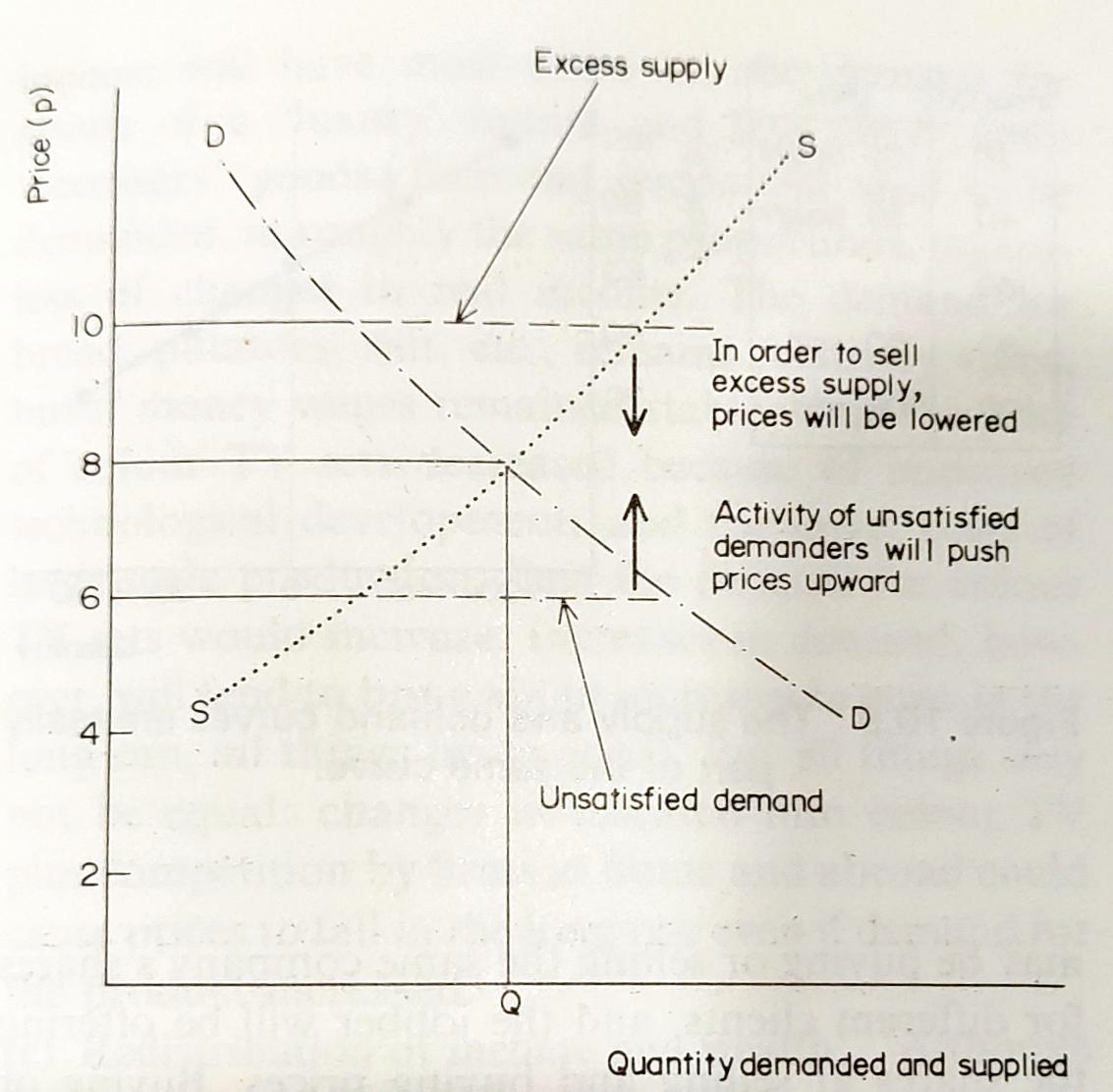

- The equilibrium price This is the price at which supply and demand are equated; the amount that producers wish to sell is the same as the quantity that consumers wish to buy.

- The market price This is the actual price on the market at any moment.

- The normal price This is the long-term equilibrium price, i.e... the market price is maintained over a comparatively lengthy period.

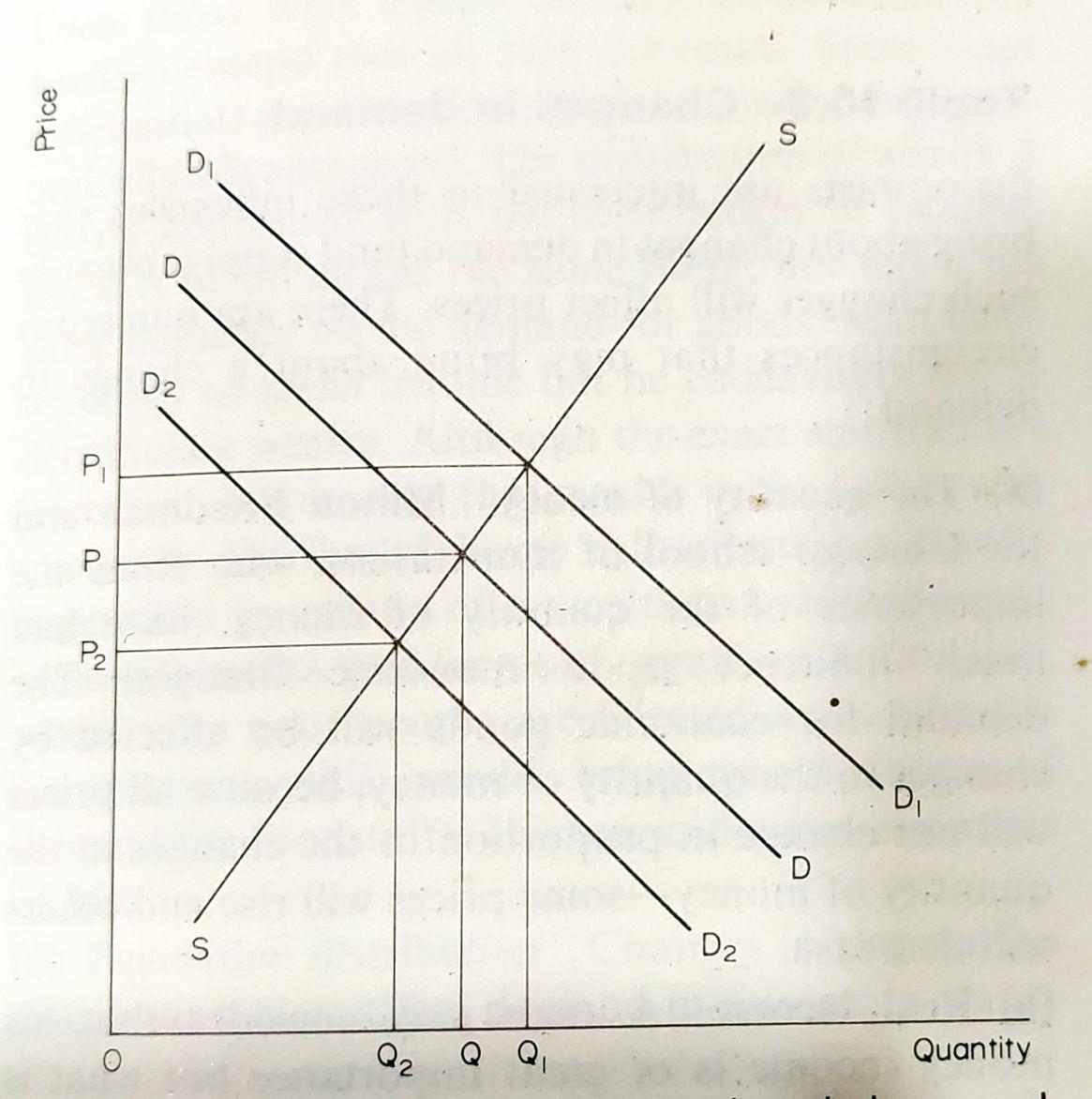

Changes in demand

- The quantity of money Milton Friedman and the Chicago school of monetarists, who stress the importance of the quantity of money, have had much influence on economic thought. The demand for economic goods will be affected by changes in the quantity of money, because of all prices. will not change in proportion to the changes in the quantity of money-some prices will rise and others will decrease.

- Real income A man may consider that his monetary income is of great importance but what is vitally important in economics is his income in real terms, i.e., what his money income will purchase in terms of goods and services. If wages lag behind prices, then real incomes will have decreased and demand for some goods will tend to decline. The changes in demand for various goods will depend a great deal upon marginal utility, which is a subjective phenomenon. It is dangerous to generalize people's attitudes, but on the whole, a change in real income will have the most effect on the demand for goods of a 'luxury' nature and less effect upon 'necessary' goods. Essential goods will tend to be demanded, in roughly the same proportions, regarding fewer changes in real income. The demand for bread, potatoes, salt, etc., remains relatively static, but if money wages remained stable while the price of colour TV sets decreased because of improved technological developments and the lower costs of large-scale production, then the demand for colour TV sets would increase. Demand increases, however, will tend to bring about price increases, in the long run, all things being equal. But all things may not be equal: changes in research into colour TV ( plus competition by firms at home and abroad could cause prices to fall in the long run even if demand for the product increased.

- Redistribution of income and wealth Although we live in a democratic society, it is not an egalitarian one; moreover, it is unlikely that such a society would be the most economically efficient. Even those who regard all men as brothers can hardly contend that all men are equal. Some wage differentials are, therefore, both necessary and economically advantageous. The distribution of wealth is connected with the distribution of income, but it is by no means the same thing; nor has it the same influence on the demand for goods. Man tends to spend income but he endeavours not to decumulate wealth. Although the exact statistics are uncertain, it is known that wealth in the UK is very unequally distributed. Some redistribution of wealth is possible using a wealth tax, higher social security benefits, and forms of negative taxation, i.e., where very poor people are allotted money by the Government, this would bring about increased demand for foodstuffs, clothes, and other essentials of life.

- Population distribution Changes in population distribution may affect demand in four main ways:

- Age distribution. If there is an increased proportion of old people in a community, there will be an increased demand for the goods that old people require, e.g., false teeth, spectacles, etc. An increased proportion of young children would bring an increased demand for preamble later, toys, etc., whereas an increased proportion of teenagers will cause an increased demand for record players, pop records, etc.

- Sex distribution. In 1975, there were 106 females to every 100 males in the UK. Ignoring age distribution for the moment, the preponderance of females would seem to indicate that demand would be greater for goods and services that are required especially by women. But demand in economics is not just a question of 'willingness and wanting; one must also have the purchasing power to make the demand effective. It is interesting to contemplate the changes in demand patterns that would materialize if the UK switched from a male-dominated society to a female-orientated society.

- Regional distribution. The UK population movements in the second half of the twentieth century have tended to be away from the older industrial areas (that evolved around the great staple industries) towards the new towns, over spills, and particularly to the 'golden triangle of the South East. Demand for goods in the metropolis has expanded rapidly. The London Allowance that is offered with various jobs is evidence enough that demand is greater and prices consequently higher in Greater London than in many other areas.

- Occupational distribution. Changes in occupations also cause changes in demand patterns. Capital equipment must be included under the classification of demand; in any economy, there is a demand for both producers' goods and consumers' goods. Today, there is little demand for the tools that accompanied the blacksmith's trade, but great demand for computers.

- Quality of goods Slight variations in the quality of branded goods leads to changes in demand and subsequent price changes. Writing in The Economic Journal in September 1970, Aubrey Silverston considered the ambiguity of the concept of price concerning the price of a car. The purchaser of a new car usually finds that the catalogue price is not the price he will finally pay.

- Advertising It is a logical step to pass from quality and optional extras to the publicity given to these things by persuasive sellers. Many of us may believe that we are not susceptible to advertisements shown on TV and hoardings, but popular writers such as Vance Packard have provided convincing examples to illustrate that advertising can change demand patterns.

- Government Governments are continually causing changes in demand because they can affect most of the influences we have considered so far. The control over the quantity of money since 1931 in the UK is almost entirely in the hands of the Government. Credit expansion of restriction, prices and incomes policies, and regional planning and legislation, all affect the demand for goods and services, e.g., the compulsion to print warnings of health hazards on cigarette packets, the use of the breathalyser, regulations to car safety belts and tyre-treads, etc. Perhaps the greatest effect the Government has on demand is utilizing its fiscal policy: an increase in excise duty on whisky or playing cards will tend to decrease the demand for these products.

- Expectation of future price changes During inflation, people will tend to demand more goods because it is preferable to hold wealth in goods, especially of a durable kind than in depreciating monetary media.

- Substitutes If there is an increased demand for goods that are directly competitive with a specific commodity, then demand will change in respect of both types of goods. Price may be the cause or the effect of demand changes. If the price of coffee is increased, then people may demand more tea; this may bring about an eventual increase in the price of tea that will cause a swing back towards coffee at the higher price. The likely long-run effect will be an increase in the prices of both commodities. In any event, a new demand pattern will emerge. All goods are in competition with one another and changes in demand, for any of the reasons being considered in this topic, would bring about a pattern of demand that would be different from that which existed before the changes took place,

- Innovations Man's inventiveness ensures that new goods are always appearing on the market and there are constant improvements to existing goods. As the demand for ladies' tights increased so the demand for stockings decreased. New goods will be considered to offer more utility than the goods replaced, but in its turn, each good is superseded by goods offering greater utility. Demand substitution constantly takes place at the margin.

- Taste British people who have holidayed in Europe may acquire a taste for wine with the result that the demand for wine will increase while the demand for beer may subsequently fall. New tastes are acquired as other factors change, e.g., real income, population distribution, inventions, etc.

- Fashion Whereas taste may be an individual thing, fashion is frequently a communal phenomenon. Inevitably, taste and fashion are linked, but movements of fashion are harder to resist. Fashion is often followed contrary to an individual's taste. The pronouncements of fashion houses, expressed through advertising, are of economic significance because by 'forcing' changes upon the community they can increase the sale of goods; last year's coat is made out-of-date and unwearable.

- Seasonal influences on Christmas trees, Easter eggs, fireworks, and Valentine cards are demanded at certain times of the year. One has only to observe the prices of flowers on Mother's Day to be convinced that increased demand pushes up prices.

- Weather The influence of weather is aligned with seasonal demand, but the effectiveness of the latter is considered in this text as extending over a long period, e.g., coat prices are influenced by seasonal demand, but cheap prices may extend over several summer months rather than over weeks or days as is the case with Christmas trees and fireworks. Examples of products whose demand is influenced by the weather include ice cream, umbrellas, and power supplies.

- Miscellaneous No doubt the student can add to this list of further influences upon demand:

- Religious beliefs. The demand by Roman Catholics for fish on Fridays or the lack of demand for pork if there were more Jews in a community.

- Vegetarians. The demand for salads, fruit, nuts, etc., is affected.

- Health. Enthusiasts may demand slimming aids, saccharines, vitamin tablets, etc.

- Conscience. If more people were persuaded that apartheid was morally indefensible, then there might be a decreased demand for South African wine and fruit.

- War and peace. Ammunition, guns, and uniforms demanded in wartime have little place in peacetime.

- Pests. A plague of wasps will bring increased demand for insecticides.

- Education. The extension of higher education brought an increased demand for books, educational buildings, and equipment.

- Metrication. There has been a need to replace goods outdated by the adoption of metrication in the UK.

- Pollution. Action to restrict pollution will change demand patterns in numerous ways. Consider the effect of declaring smokeless zones and research on exhaust fumes emitted from cars.

- Expectations of future trade The demand for both consumer and capital goods may be affected by anticipations of trade trends. This type of demand forecast is known as a projection.

- Status symbols There is an increased demand for cars in August each year when a new letter appears in the registration.

The intending purchaser may find that he can get a de luxe model, but that it may prove very difficult to get a standard model, which is what he wants... The purchaser may derive utility from the de luxe elements in the car, but this will not be sufficient to compensate him for the higher price. Consumers tend to be demanding, perhaps unwittingly as Silverston suggests, higher-priced goods of superior quality.

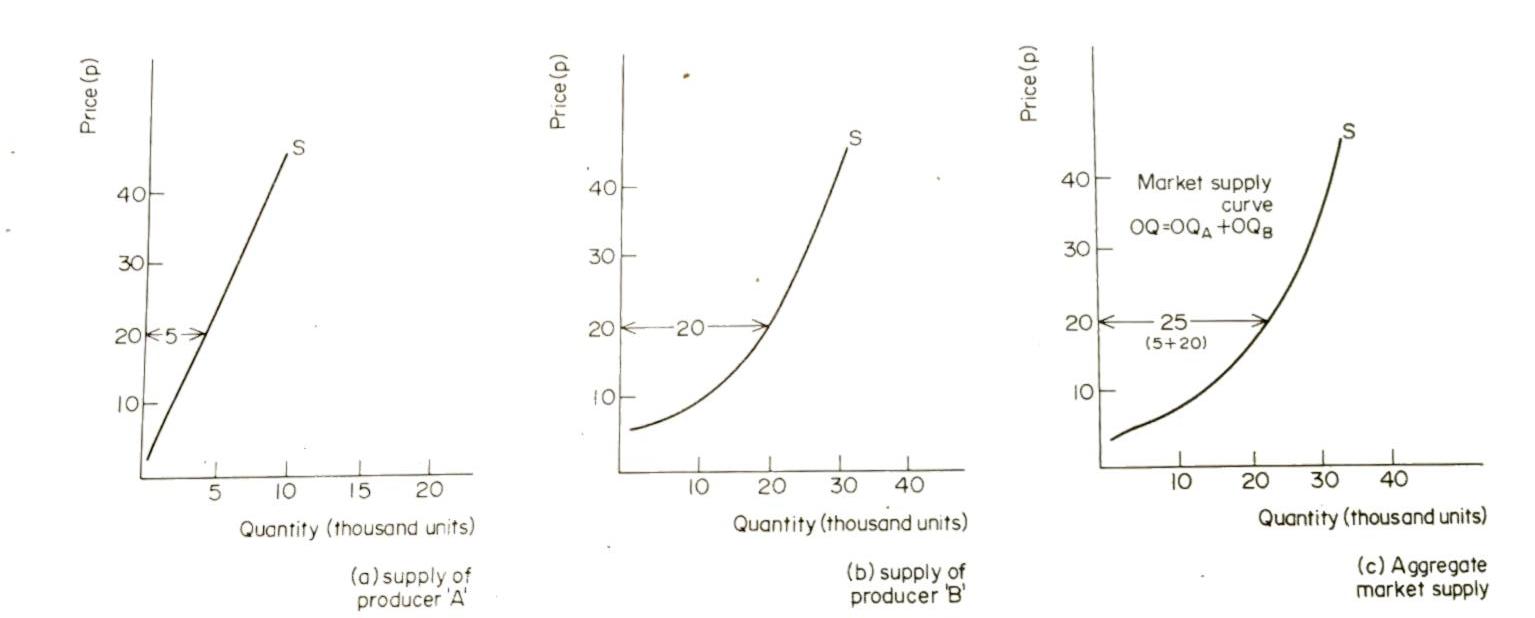

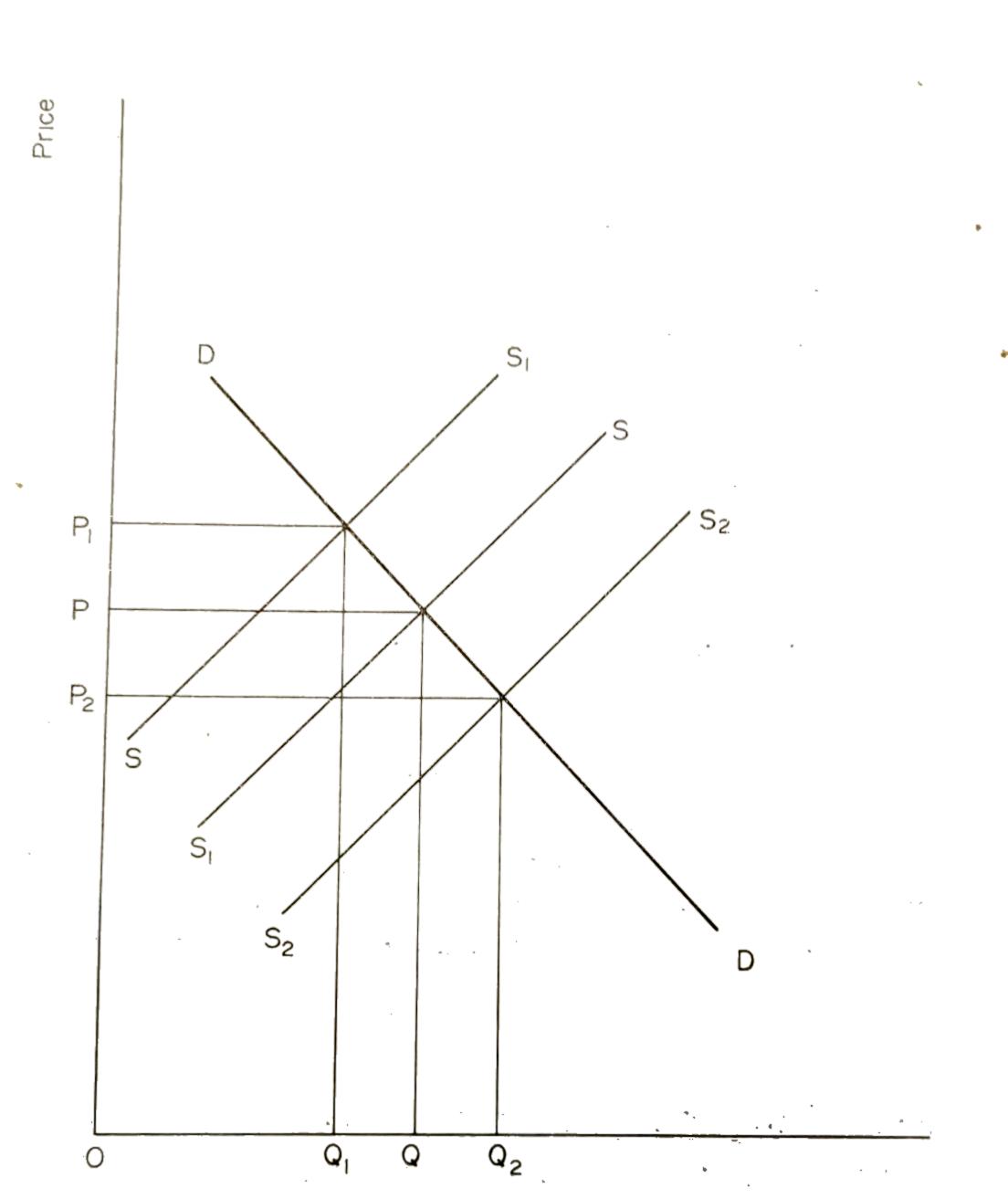

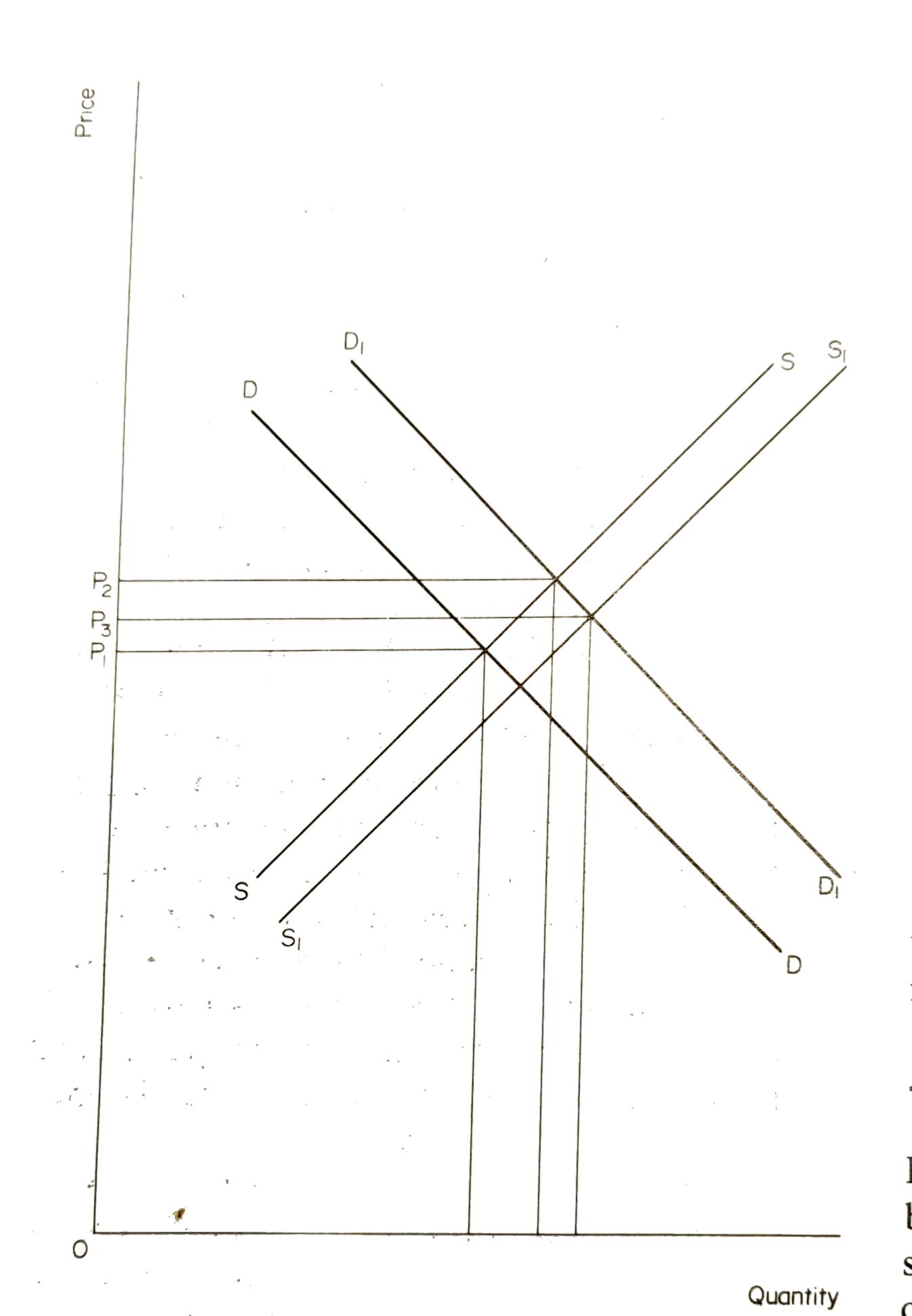

Topic 10.4 Changes in supply

- Changes in supplies of minerals New mineral supplies may change the world supply pattern. For example, deposits of columbite, used for the metallic filaments of electric lamps, are almost entirely confined to Nigeria; any major discoveries elsewhere would have great significance. Some mineral supplies are being expended, or may cease to be worth mining; for example, the UK has enough coal to last for over 200 years at the present rate of production, but probably much of it will never be mined as seams are thinner and less accessible, and other fuel sources, such as oil and gas in the North Sea, are being discovered all the time. The economist is concerned with effective supply, i.e., the supply that comes onto the market.

- Growing conditions The supply of agricultural and horticultural products is particularly influenced by external factors, often beyond the control of men, such as fire or unusual weather conditions. Whether it is a year of scarcity or abundance will influence prices, although the work of speculators may have a levelling effect.

- Man's influence Man is constantly exerting an influence upon Nature. He may improve conditions through irrigation, fertilization, insecticides, soil conservation methods, etc. The man may misuse Nature's gifts by overfishing or soil erosion, and so the supply of certain commodities will be reduced. Man has become preoccupied in the seventies with the problems of pollution and the need for conservation. The supplier of primary products has to be careful that he does not disturb the balance of nature. The destruction of the apple boll weevil by insecticides led to the production of apples the size of marbles and the next year extra labour had to be engaged to thin out the blossom by hand.

- Government influence During the two world wars of the twentieth century, belligerent governments rationed the supply of many products, especially foodstuffs. The Suez Crisis of 1956 compelled the UK Government to ration the supply of petrol. Sanctions against Rhodesia decreased the effective supply of tobacco available for world consumption.

- Producer country consumes more of its output If a country has been relatively poor and has been forced to export a large proportion of its supply of a product to maintain a reasonable standard of living, when that country becomes more prosperous it may be able to consume more of its products and thus the supply to the rest of the world will be reduced. India, Japan, China, and Egypt consume much of their raw cotton for manufacturing, whereas until 1913 the UK was the largest supplier of finished cotton goods.

- Power There are so many ways in which men may increase their sources of power; wood, peat. wind, water, coal, gas, oil, and atomic energy have all been utilized. Supplies will change as old sources of power are discarded and new sources are discovered. Power prices have a deep-rooted effect on the supply of other products.

- Cheaper raw materials many of the influences upon supply are interrelated. Thus an improvement in power that helped in the production of cheaper and plentiful steel would make possible the increase in the supply of all those things made from steel motorcars, washing machines, refrigerators, air-liners, cutlery, computers, etc. Technical improvements and rationalization may result in production on a larger scale.

- Management and organized labour In recent years, the UK have often lagged in increasing the supply of manufactured goods because of the restrictive practices of both management and men. The application of time and motion study techniques will often increase the supply of goods. Supply depends upon the entrepreneurial organization that underlies productive methods. Wages, or the price of labour, affect supply; if wages rise, the cost of production will increase and the supply of the product may well decrease unless the producer can cut his costs in other ways. Industrial unrest curtails the supply of products.

- Profit Suppliers attempt to maximize their profit. The profit motive will encourage producers towards more research and capital investment which may lead to an increased supply; lack of capital, research and new inventions will hinder efforts to increase supply. Some monopolists may deliberately diminish the supply to keep up prices. Thus, fish have been thrown back into the sea in the UK, cotton crops ploughed into the ground in the USA, ships broken up in West Germany, and coffee beans burned as locomotive fuel in Brazil. The supply may be artificially controlled by agreed quotas.

- The population explosion In an attempt to feed the increasing world population, the United Nations and its various agencies have helped to increase essential supplies throughout the world (see Topic 4.2).

- Anticipated future demand Production takes place in anticipation of demand, although it would be wrong to consider the demand curve and the average cost curve as independent variables. The average cost of producing an article is made up of all costs (both fixed and variable) including selling costs. A successful advertising campaign may increase the overall costs of production but may well cause the demand curve to move to the right, indicating an increased demand for goods that have already been produced.

- Substitutes Many of the influences that we studied as causing changes in demand, influence supply, and vice versa. Therefore, we need only consider them very briefly in this section. We saw how the price of substitutes brought changes in demand, and clearly, a new supply pattern will emerge as price movements take place where commodities are in competitive or alternative demand.

- Speculators The work of speculators will affect demand although, by such activities as arbitrage, hedging, dealing in futures, etc., their fluence will usually tend to regularize supply in the long run.

- Marketing boards Other stabilizers of supply are the British Marketing Boards. The first Acts setting up Marketing Boards were passed in 1931 33, and the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1958 consolidated earlier legislation. Marketing Boards are producers' organizations with legal powers to regulate the supply and marketing of products under their jurisdiction.

- Miscellaneous As was the case with changes in demand, it does not mean that the influences listed briefly below are of less importance than those already studied. Indeed, a case could be made out that many things enumerated as miscellaneous provide some of the most important influences on supply patterns:

- Seasonal scarcities and gluts. A good crop of Cox's Orange Pippins may mean that apples can be bought for 30p a kilo, whereas if the next crop is bad, one may have to pay 40p a kilo. Seasonal influences affect the supply of flowers, vegetables, etc.

- Regional tastes. Despite the greater uniformity of supplies that accompanies branded products, there are still specialized supplies to meet area tastes, e.g., black puddings in the Midlands and haggis in Scotland. This point is so closely linked with demand as to be almost inseparable.

- Livestock diseases. For example, an epidemic of foot-and-mouth disease, and government policy towards such catastrophes, will affect supply. If government regulations state that all cattle infected with the foot-and-mouth disease must be slaughtered, then not only will drastic reductions in supply take place in the short run, but, in the long run, supply will be seriously curtailed as it takes time to build up herds of cattle.

- Patriotism. Campaigns and slogans exhorting consumers to 'Buy British' stimulate the supply of home-produced goods. However, patriotism does not always coincide with economic motives and the supply of foreign cars to the UK has increased greatly in recent years. Following the principle of comparative costs, each country should supply the good or service in which it has an economic advantage. However, to give employment to workers within a country, governments offer subsidies, grants, and allowances to help home suppliers compete effectively. Whether or not home suppliers should receive government help is largely a political question.

- Laws. The so-called permissive society, with its acceptance of material that would have once been regarded as pornographic and morally harmful, has brought about an increase in the supply (and subsequent demand) for a whole range of products

- Leisure pursuits. Readers of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (Chatto and Windus) will recall that all kinds of mechanical sports were supplied to the masses in an attempt to keep them contented. When one sees so-called experts forecasting the results of matches for the organizers of football pools, and synthetic TV programmes, one finds it almost frightening to see how true were Huxley's visions of the future. Mass marketing techniques can affect both supply and demand.