Some writers of economics textbooks have declared categorically that the value of money is determined in the same way as the value of other economic goods. However, although the supply of money and the demand for money are the most important factors influencing the value of money, there is little doubt that money deserves separate treatment from that provided by the microeconomic approach alone. Otherwise, why is it that economists have for centuries attached special significance to the value of money? If the value of money could be analyzed in the same way as any other economic good, why is it that money has long been treated as a special case? As David Laidler points out, in The Demand for Money: Theories and Evidence (International Textbook Company):

Textbooks of microeconomics do not contain chapters with titles like 'The Theory of the Demand for Refrigerators', but rather present a generalized analytic framework in terms of which the demand for any good may be treated.

There are several important reasons why the value of money calls for a separate treatise:

- Normally when the supply of an economic good is increased there is a fall in the value of that good, and if demand is assumed to be constant prices will tend to fall. In the case of money, an increase in its supply will tend to cause the value of money to fall, but the prices of other economic goods will tend to rise, i.e., there will be inflation. The monotonous use of the word 'tend' must be tolerated because, in certain unusual circumstances, counteracting forces may produce a different result from the one usually expected.

- Where as such commodities as refrigerators do not exert any special influence over economic forces (for a new refrigerator in a shop is a passive article), money plays a dynamic role of its own. Money fulfills an active function through its influence on the price system:

- The market value of money is relatively predictable because it is universally acceptable. Apart from a few ascetics, such as the followers of St Francis of Assisi, almost everybody wants money. This can hardly be claimed for all economic goods; the phenomenon arises because money possesses liquidity.

- The supply and demand for money are not determined by normal use-value criteria. Only an abnormal person, such as a miser, wants money for its own sake. It cannot satisfy hunger, quench thirst, or move a person from place to place. Other commodities are supplied and demanded because they give utility and act according to the principle of the diminishing marginal rate of substitution between other goods. Not so with money. The more one has, the more one wants. The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility seems to have little effect on its value.

we have discovered money, the intermediary, leading a life of its own. Instead of acting merely as an accounting mechanism, it exerts an influence of its own on all prices. It is as if the yardstick started monkeying with the lengths. (Crowther, An Outline of Money, Nelson.)

Money refuses to be neutral: it insists on playing a role of its own, and is, therefore, different from any other commodity that waits passively for its price to be determined by the interaction of market forces.

Having qualified the rather sweeping statement of those who assert that supply and demand are the sole and simple determinants of money, we have to return to the position taken up at the beginning of this topic by admitting that (although the value of money is more complex than the value of economic goods), the supply and demand for money do exert an important influence upon its value. We must therefore examine briefly what constitutes the supply of money and the demand for money.

The Supply of Money

In modern economic society, the supply of money comprises two main sources:

- Currency Currency circulation consists of coins and notes. Since 1931, the UK currency issue has been controlled by the State. Coinage is produced at the Royal Mint which buys metals and pays for the manufacture of coins that are sold to the Bank of England. As the UK coins are now all token coins made of bronze or cupro-nickel, the Royal Mint makes a substantial profit; since decimalized tion in 1971, there is no British coin that costs more to mint than its face value. Coinage is only a small part of currency circulation.

- Bank money Figure 16.2 indicates that the total money supply includes deposits held by financial institutions. The student who has little knowledge of the workings of the monetary system may be excused from wondering how financial institutions can hold more 'money' than there are notes and coins in the country. Deposits are increased by the bankers' power to create credit. From 1947, bankers maintained a minimum cash reserve ratio of 8 percent (5 percent in their tills and 3 percent in their accounts with the Bank of England), and in theory, they continued lending until hypothetically about 12.5 times the original amount of additional credit had been created. The true credit base, until 1971, was the liquid assets ratio, for the banks aimed to maintain the 28 percent short-term liquidity stressed as desirable by the Radcliffe Report of 1959.

- All financial institutions, including the clearing banks, were treated in a more uniform method to control credit expansion.

- The rate of interest (which is the main pricing mechanism concerning credit) was used to allocate credit; credit rationing by quantitative control was largely abandoned.

Bank of England notes form by far the greatest proportion of UK currency (see Fig. 16.1), although Scottish and Northern Ireland banknotes still circulate, largely within their own countries.

Both notes and coins reach the public by way of the clearing banks; if the public's liquidity preference increases, there will be increased withdrawals of notes and coins by the holders of bank accounts. To maintain a satisfactory cash float, commercial banks will obtain more notes and coins. from the Bank of England and have their accounts with the Bank debited accordingly.

The scope of the banks' powers to create money was radically transformed by the Competition and Credit Control (CCC) policy which was inaugurated in 1971.

To facilitate credit control the concepts of eligible liabilities and eligible reserve assets were introduced. Under the Competition and Control scheme, all banking institutions had to keep, day by day, a minimum of 12.5 percent of eligible liabilities in the form of eligible reserve assets. The eligible reserve assets ratio replaced the old 8 percent cash and minimum of 28 percent liquid assets as the fulcrum around which control of the credit system worked.

Eligible liabilities were defined as the sterling deposit liabilities of the banking system as a whole, excluding deposits having an original maturity of over two years, plus any sterling resources obtained by switching foreign currency into sterling.

Figure 16.1 Changes in note circulation from 1977 to 1980.

(Source: Bank of England Report and Accounts", 1980.)

Figure 16.2 UK money supply.

(Source: Barclays Bank plc.)

Eligible Reserve Assets

- Balances with the Bank of England other than Special Deposits.

- British Government and Northern Ireland Government Treasury Bills.

- Money at call with the London money market.

- British Government stocks and nationalized industries' stocks guaranteed by HM Government with one year or less to final maturity.

- Local authority bills eligible for rediscount at the Bank of England.. (f) Commercial bills eligible for rediscount at the Bank of England up to a maximum of 2 percent of eligible liabilities.

New Money Supply Arrangements From 1981

From August 1981, there have been new monetary arrangements affecting the creation of credit by the banks. The Reserve Asset Ratio (RAR) has been abolished and the foundations of the 1971 Competition and Credit Control system have been removed. There are three important reasons why the 1971 policy was abandoned after 10 years of operation.

Firstly, the RAR proved in practice to be an extremely blunt monetary instrument. It was an artificial pivot for influencing interest rates, and banking practice indicated that the RAR was largely divorced from the real world.

Secondly, the 1971 arrangements discriminated against the London clearing banks as they had maintained 1.5 percent of their eligible liabilities in the form of balances at the Bank of England. This discrimination was removed in 1981 with the underlying idea of increasing the level of competition in the banking sector as a whole.

Thirdly, the standardization of the reserve assets ratio did not take into account particular banking demands. Thus, since 1981, the liquidity ratios have been negotiated individually for each bank based on particularistic criteria. General guidelines have been formulated but within these, there is much more room for flexibility.

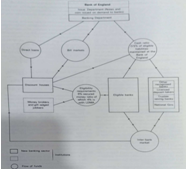

There are three main provisions of the system introduced in 1981. Firstly, all eligible banks, licensed sed deposit takers, trustee savings banks, and the National Giro must keep a 0.5 percent cash ratio of eligible liabilities in deposits at the Bank of England. These balances are non-interest bearing. The London clearing banks are, in addition, required to keep whatever level of operational balances at the Bank of England as deemed necessary to meet its day-to-day needs.

Secondly, there is the stipulation of a 6 percent secured money ratio of the eligible banks' eligible liabilities, including a 4 percent minimum holding with the London Discount Market Association (LDMA) (see Fig. 16.3).

Thirdly, short-term interest rates will be much more responsive to market trends with the proviso that the Bank of England will, when desired, act to fix short-term rates at some desired level, through its Open Market Operations.

Conclusion

The banks' power of credit creation is limited by:

- The amount of money in circulation.

- The Government's current monetary policy.

- The public's liquidity preference.

- The banks' assessments of the security or collateral offered.

- The requirement of the clearing house system that commercial banks expand or contract credit concurrently-one bank cannot adopt a policy that is out of step with other banks or it will lose deposits to the other banks within the system.

- The amount of cash held by the bank immobile wealth is taken, made mobile, and increased (by credit creation).

The measurement of the supply of money depends on the definition of money. The Bank of England published measurements based on two official definitions.

- The narrower definition (M1) comprises current account balances with banks plus notes and coins in circulation.

- The broader definition (M3) is enlarged chiefly by the addition of deposit accounts, deposits of the public sector, and deposits held in currencies other than sterling. The broader measurement, M3, is regarded as more important in the UK. Whichever measurement is taken, notes and coins form a relatively small part of the total money supply (see Fig. 16.2).

Figure 16.3 The UK banking sector.

(Source: Barclays Review, November 1981.)

The Demand for Money

The demand is derived from three main sources:

- Individuals and households for the consumption function.

- Individuals and business undertakings for the investment function.

- The Government for the State expenditure function.

These three sources are interrelated with each other and with other economic phenomena. Consumption, for example, is an increasing function of disposable income and is dependent upon wages, prices, and employment. Investment is related to the rate of interest and liquidity preference. Government expenditure is related to government borrowing and taxation. The demand for money is a complex subject and we have time only to explore the foothills.

The basic principle governing the demand for money is that as money is a generally accepted medium of exchange, the demand for it increases with income. The second law of Professor Parkinson that 'expenditure rises to meet income' may be humorous, and realistic to the student's experience, but it also contains a basic economic truth underlying the demand for money. If people do not hold money, then they will hold other assets, e.g., durable assets, diamonds, gold, Krugerrands, National Savings Certificates, stocks and shares, or the like. Individuals have to decide in what proportions of money or other assets to hold their wealth. The problem centers around how much money to hold and this will depend on:

- The level of income.

- Liquidity preference.

- Rates of interest.

- The state of trade.

- Inflationary or deflationary trends.

The demand for money varies with liquidity preference. Keynes suggested that there are three especially important motives for holding money in the sense of an individual's preference for money over other assets.

- The transactions motive One demands money to pay one's normal day-to-day bills depending upon the changing patterns of consumption. In a period of sharply rising prices, the amount of money demanded by the transactional motive increases.

- The precautions motive Money is needed to cover unforeseen contingencies. Even if no definite transaction is intended, people carry money 'just in case. Both the transaction and precautionary motives for holding money apply to firms as well as individuals.

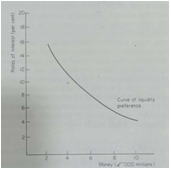

- The speculative motive The amount of money held back for speculative purposes depends upon the community's subjective estimate of future bond (or security) prices. Few poor people will be involved in speculation as they will have a little surplus for this purpose. More affluent people and permanent institutional investors, such as insurance societies, may well hold back money for the time being hoping for a future increase in the prices of stocks and shares. In such a case they are holding money for the speculative motive. The higher the rate of interest the less will be the desire to hold money for speculation (see Fig. 16.4).

In recent years Milton Friedman and the monetary ist economists have provided a new analysis of the demand for money and, in particular, its effect on aggregate demand. For monetarists, the demand for money is influenced by two main factors:

- The rates of returns on money and other assets (both real and financial);

- The level of income.

Keynes held that money had no real substitute save alternative financial assets. Monetarists assert that. in certain circumstances, goods and services provide the alternative to hold money instead of other financial assets.

The key issues concern, firstly, the stability of money demand, and, secondly, the results in economic terms when money demand is thrown into disequilibrium. Regarding the first point, Friedman does not attempt to argue that the demand for money is a constant. Indeed, the velocity of circulation (V) is looked upon as being subject to change. However, theoretically and empirically there is little evidence of rapid changes either in Vor money demand (Md): and it is precise because of these slow and predictable changes that the modern quantity theory is realistic and of practical application (see Topic 16.7). However, according to monetarists, the money supply is subject to rapid change. This suggests that the money stock is fed primarily by supply changes. and that money supply and money demand are independent. According to Friedman. The conclusion is that substantial changes in prices or nominal income are almost invariably the result of changes in the nominal supply of money (M. Friedman, Quantity Theory, International Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 10).

The independence of money supply and money demand also has ramifications for the question of interest rate effects. Monetarists are forced to contend that monetary demand is interest inelastic. If this were not the case an increase in the money supply, producing corresponding effects on interest rates, might well affect money demand, and so bring into existence a new money demand and supply equilibrium. Not only would money demand and supply then be interdependent' but one could not predict the outcome of the increased money supply, for the ratio of money demand to money income would not be disturbed. In short, one could not assume that the additional money stock would be off-loaded in the form of increased (ultimately inflationary) expenditure.

Figure 16.4 The liquidity curve indicates how much liquidity individuals demand the speculative motive at different rates of interest.