Avail Your Discount Now

Discover an amazing deal at www.economicshomeworkhelper.com! Enjoy a generous 10% discount on all economics homework, providing top-quality assistance at an unbeatable price. Our team of experts is here to support you, making your academic journey more manageable and cost-effective. Don't miss this chance to improve your skills while saving money on your studies. Grab this opportunity now and secure exceptional help for your economics homework.

We Accept

Understanding budget is very important if one plans on making a career in the finance sector. Students avail economics homework help for homework based on budget due to a lack of understanding. Let us try to understand in detail what a budget is. The Budget, an estimate of government expenditure and revenue for the coming year, is usually presented to Parliament by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the spring of each year. In times of emergency, there may have to be interim budgets. Until 1962, the Economic Survey was issued just prior to the Budget, but this was superseded in that year by the Economic Report, which examines the course of the economy during the previous year and contains an assessment of its performance.

Detailed estimates of the government’s expenditure

The detailed estimates of expenditure prepared by each government department for the financial year ahead are made within a broad long-term framework. They are submitted to the Treasury towards the end of each calendar year for an examination so that the Treasury can ensure that the proposed spending is in line with the agreed policy and is a reasonable estimate of what is likely to be needed. The agreed estimates are published in March and submitted to the House of Commons. So that the business of government can be carried on, the House of Commons approves a sum "on account' for each department (usually enough to last until about early August). Before its summer recess, the House debates the policy issues involved before authorizing the rest of the spending. On detailed tax questions, the Chancellor is advised by officials of the Inland Revenue and Customs and excise; on economic and financial policy, he is advised by officials of the Treasury.

Years ago, budgetary measures (or fiscal policies) were looked upon merely as a means of raising revenue. It is now realized that the budget may be used as an instrument of economic policy. When preparing his Budget, the Chancellor considers three main questions:

- How much the Government will need to spend in the coming year?

- How much money taxes will raise if no changes are made in the rates levied?

- The country's economic prospects, e.g., mitigating the evils of mass unemployment and too high a rate of inflation.

This principle of using taxation as an instrument for the direction of economic policy was made clear in the 1944 White Paper, Employment Policy, which recognized no merit in a rigid policy of balancing the budget each year, regardless of the state of trade. Such a policy is not required by statute, nor is it part of our tradition. The Chancellor of the Exchequer takes into account the requirements of trade and employment in framing his annual Budget. The Budget Day proposals are important as they are only part of a government's measures to implement its economic policy. It has to keep the state of the economy and the need to regulate it, under review throughout the year. Some economists consider that the budget is an outdated annual ritual that ought to be replaced by more frequent adjustments such as packages of economic measures introduced from time to time in an attempt to obtain more flexibility. There have also been advocates of long-term anti-cyclical budgets with an influence extending over five, seven, or even ten years.

Taxable capacity

It has been suggested that there is an upper limit to the amount that a government can take in the form of taxation. Taxable capacity will be reached when the economy is harmed by excessive taxation. For example,

- Production may suffer if very high taxes deter workers from doing overtime.

- Enterprise may be hindered if high taxes result in a 'brain drain' of top managers and scientists.

- Private investment might be deterred by excessive rates of corporation tax and capital gains tax.

- High indirect taxes may well prove inflationary and bring forth a spate of wage demands combined with industrial unrest.

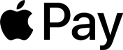

- If a commodity tax was subject to elastic demand, it is possible that the Chancellor would receive less income from an increased tax if the demand for the commodity fell away steeply (see Fig. 8.5)

Professor C. Clark, in Taxman ship (Hobart Paper 26, Institute of Economic Affairs), maintained that if the level of taxation exceeds 25 per cent of net national income, inflation will follow. He has argued that a high tax level reduces the supply of factors of production and makes entrepreneurs careless about costs, thus reducing their resistance to higher interest charges and wage demands, which incidentally, are encouraged by high rates of taxation. Although Professor Clark's arguments are logical and supported by empirical studies, it seems rash to be precise about the level at which taxable capacity occurs.

The 'Balanced' Budget

Fiscal policy

The Chancellor's task is to juggle the tax structure and tax rates so that we have economic stability (see Fig. 8.6). If one aspect of the economy is in a bad way, the Chancellor takes measures to correct it, but his action may be disadvantageous to other parts of his economic policy. It is generally agreed that the government should take measures:

- To keep inflation in check.

- To promote full employment.

- To secure economic growth.

- To avoid a large and long-standing balance of payments deficit.

- To promote social justice.

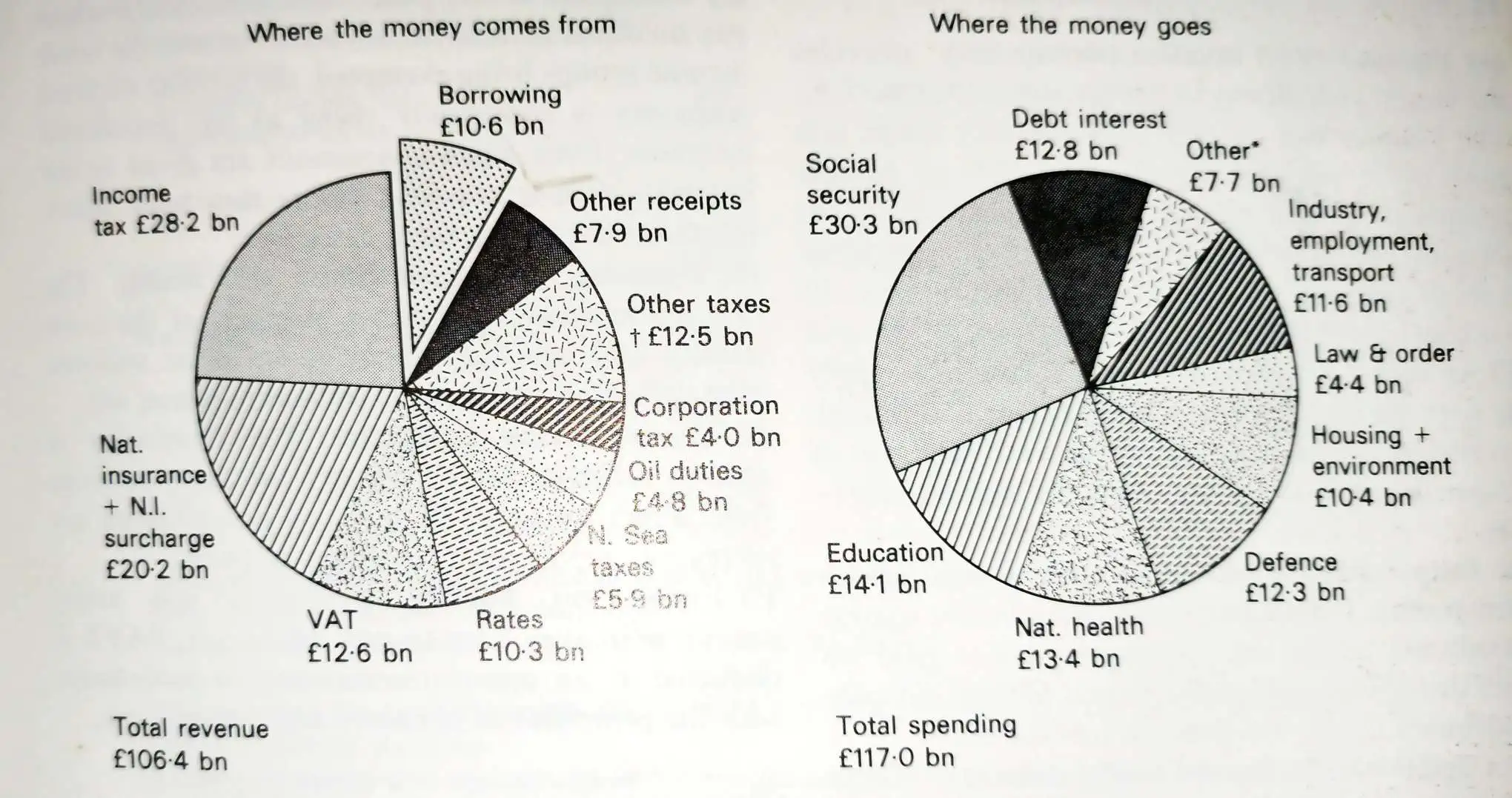

Figure 8.6 Public income and expenditure 1981 to 1982 (Source: Financial Times, 10 September 1981. Economic Progress Reports.)

You Might Also Like

Delve into a trove of knowledge and insights with our captivating blogs. From expert tips to industry trends and innovative solutions, discover fresh perspectives on topics that resonate with you. Stay informed, inspired, and empowered as you explore our latest posts.