Avail Your Discount Now

Discover an amazing deal at www.economicshomeworkhelper.com! Enjoy a generous 10% discount on all economics homework, providing top-quality assistance at an unbeatable price. Our team of experts is here to support you, making your academic journey more manageable and cost-effective. Don't miss this chance to improve your skills while saving money on your studies. Grab this opportunity now and secure exceptional help for your economics homework.

We Accept

Although a student may have a reasonable understanding of the scope of economic science, he is unable to study the subject at any advanced level until he has mastered the meaning of the main economic terms. Due to this, the student might need to avail assistance with economics homework and spend more time understanding basic topics. As with all sciences, economics has its own jargon or terminology. Sometimes it is necessary to use a word in a slightly different way from ordinary speech; otherwise, the economist would have to invent new words or adopt rather peculiar terms. Writers of economic textbooks have often been at variance over the use of terms. Professor Heinz Kohler believes that beginners are typically swamped with language, which contributes to confusion instead of understanding' (Scarcity Challenged, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston). It is the aim of this blog to clarify some of the basic economic concepts in terms that the majority of economists would accept

Wealth

Economics began with a study of wealth, and, therefore, our first task must be to clarify our ideas about what constitutes economic wealth. In order to be considered as wealth, in an economic sense, goods and services must possess three main attributes:

- They must be desired because of some satisfaction -10% of which they offer A very old program football match may be of no value to most people, but it may become valuable if it is desired by a collector.

- They must be relatively scarce The stones on the sea-shore would not normally be regarded as wealth because they are in abundant supply, but certain types of stone would become wealthy if they could be utilized as building materials,

- They must be capable of being transferred from one person or group of persons to another person or group It is even possible to transfer intangibles, such as business goodwill or milk round, but some things cannot be exchanged. For example, it is not possible for a man, who has good hearing, to pass on to a deaf man the ability to hear. However, if it is possible to pass on the cornea of the eye to give eyesight to a blind man, the cornea could become an object of wealth

At least one economist has laid down the condition that before goods can be considered wealth, they must have a monetary value. This requirement would be necessary for modern economic society. but really arises from the three criteria already considered, i.e., desirability, scarcity, and transfer ability. In a barter economy, it would be possible to possess wealth without goods having a monetary value.

The distribution of wealth is of utmost importance to the economist if scarcity is to be realistically challenged.

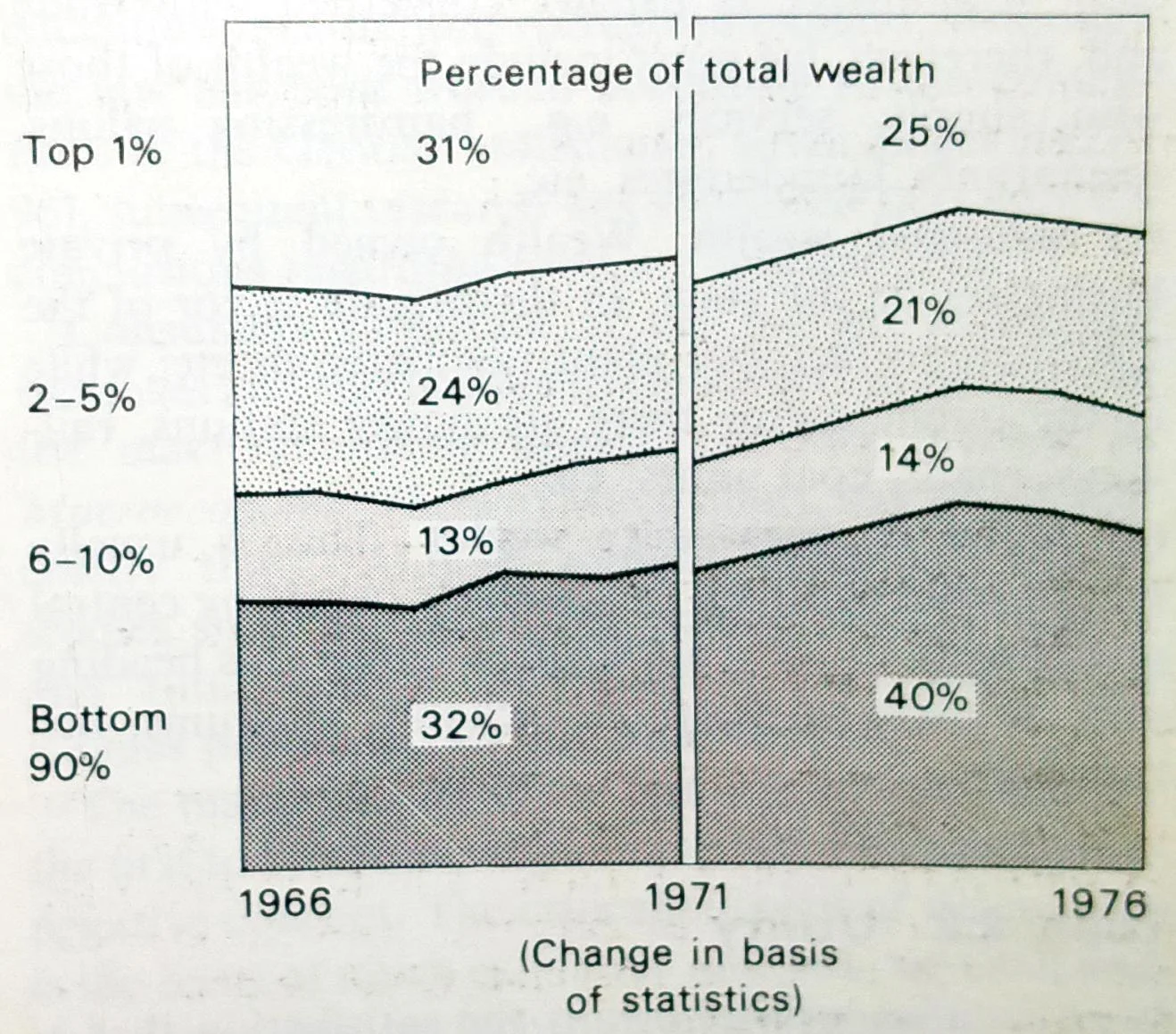

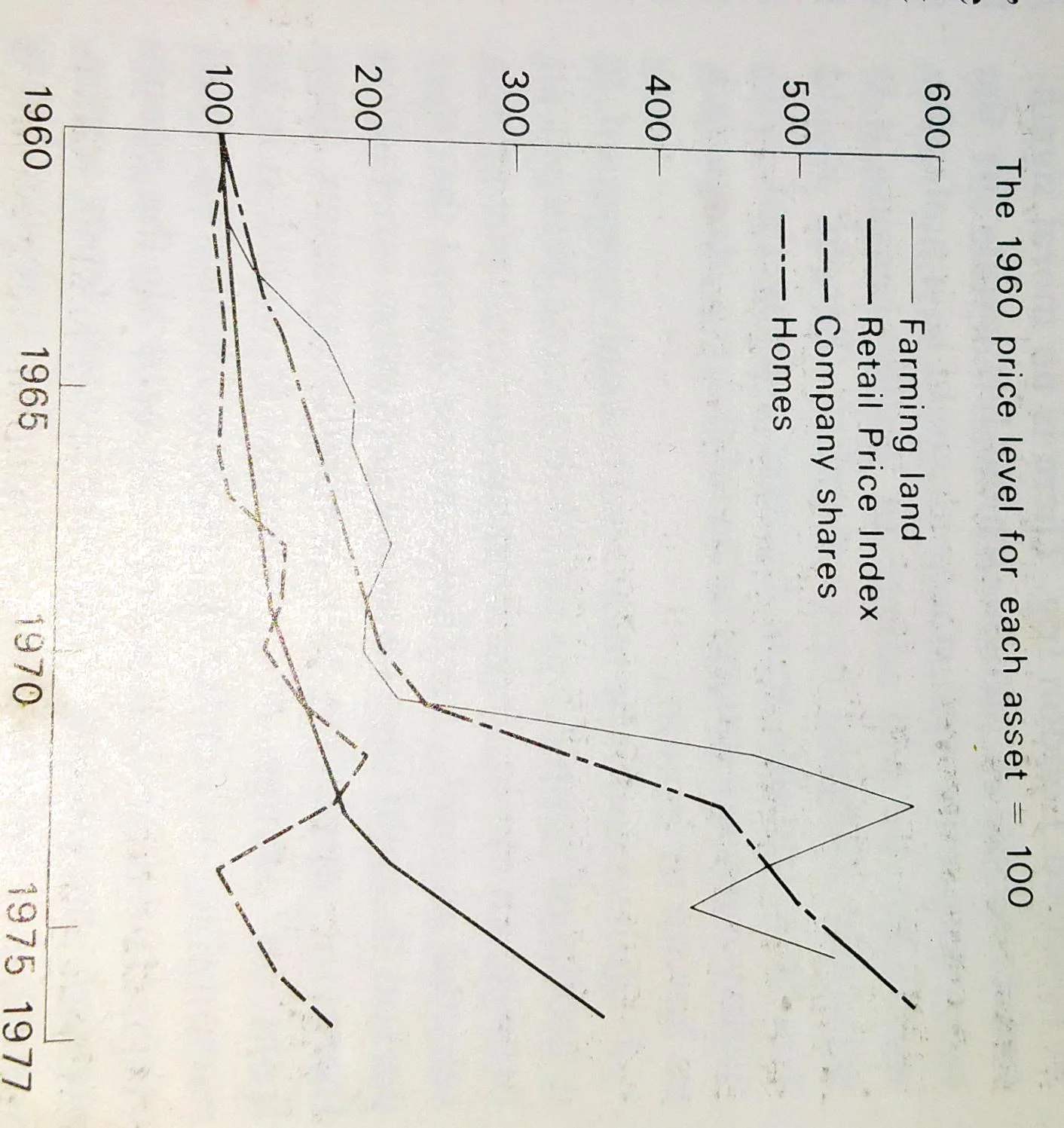

Over recent years, there has been a great disparity in the values of different types of wealth tee Figs 21 and 2.2). Land and property have increased dramatically in value. while share prices have remained relatively static.

Figure 2.1 The spread of wealth over the years.

(Source: An A to Z of Income and wealth, HMSO)

Figure 2.2 Kinds of wealth (Source: An A to Z of Income and wealth, HMSO)

The ownership of wealth

The ownership of wealth may be broad classes:

- Individual wealthEven in a collectivist society, one would presumably want to posers one's own toothbrush,

- Commercial wealth(eg, shops, banks, offices, etc.) Commerce is usually concerned with trade and, therefore, we include the wealth of those who supply services, eg, hairdressing salons, restaurants, launderettes, etc.

- Industrial wealthis Wealth owned by private businesses or the state. In the private sector of the UK, there are factories, plants, raw materials; etc, while in the public sector there are power stations, railways, roads, coal mines, etc.

- Social or community wealth This is usually ownable collectively on the people's behalf by central government or local authorities. Under this heading may be included hospitals, schools, museums, libraries, etc

Utility

In economics "utility means the satisfaction that a person gains from a certain article. It is not necessary that the article which satisfies should be a useful article Some people are willing to pay 50p for a tin of so-called London fog. There is no moral significance about an article that has utility in the economic sense Satisfaction would be a preferable word, but we will adhere to the utility because it is generally accepted by economists. The benefit would not be a suitable term because a thing that gives "utility may not always be beneficial, eg, drugs such as heroin or opium.

Utilities cannot be measured but only compared. If a group of people was asked to choose between an orange, an apple, and a banana, and only one person selected an apple, the choice would suggest that that person thought that he would gain more satisfaction from the apple on this particular occasion, than from an orange or a banana It would not be reasonable to infer that he preferred apples above all other fruits or that. compared with all the people present, he gained the most satisfaction from apples. Some other person present might have obtained very great satisfaction from an apple, but even more satisfaction from an orange. The person making the choice might not have a great liking for fruit, but of being divided into four choices presented the apple gave the greatest satisfaction. One can only compare utilities and attempt to maximize satisfaction by arranging one's expenditure in the way in which it is thought that the greatest utility will be obtained. Utility essentially depends upon a person's subjective estimate of the satisfaction that he hopes to obtain from a particular commodity or service (Some economists use the term 'disutility to describe activities in which people would rather not indulge: many people would rather not work, and, therefore, must be paid to do it, however, the term 'disutility involves a rather negative approach and does not appear to have much useful economic significance.)

Scale of preferences

The arrangement of purchases in an order of preference, in an attempt to gain maximum utility, is lib-known as a scale of preferences Subconsciously, we all indulge in the practice of building up such a scale depending largely on the satisfaction which we expect to gain from the goods or services upon which we spend our money. We may be disappointed and if we had the opportunity over again we would not allocate our expenditure in that particular way. All expenditure is to some extent made in expectation of the utility which the purchaser thinks he will obtain. A man may pay 15 to see his favorite soccer team. but if the side loses five nil, then he will not have the satisfaction that he anticipated. Unfortunately, it would be useless for him to request his money back. Each person has his own scale of preferences; the arrangement of utilities that he wishes to satisfy will be very flexible and dependent upon changes in Income plus the satisfaction obtained from past expenditures. If his income increases, he may decide to buy a car and might then have less to spend on cigarettes. If the football team which he usually supports is losing most of its matches, he may cease to spend any of his money on admission charges to soccer matches.

The origin

It is generally assumed that there is a minimum expenditure that must be made in order that any utility can be gained. It is possible to buy a gallon of petrol, a box of matches, or a newspaper. In some circumstances, it would be convenient to a customer if the newsagent could be persuaded to tear off the are rarely concerned with total utilities, but with sports page and sell that for 1p, but it would be a marginal utility: we may spend a little more on unconventional and unlikely practice. The minimum holidays or central heating and a little less on food practicable purchase is known as the origin The and clothing. This change in family expenditure football spectator has to pay to watch the whole would be in accordance with Ernst's Law which game cannot expect any money to be refunded if states that as income rises the percentages spent on food and housing decrease on clothing and household operations remain about constant on education, health, and recreation expand. Although the law has been worded according to the contentions of the German statistician, Ernst Engel (1821 96), subsequent research has suggested that only his conclusions regarding food are indisputable he leaves in disgust at half-time

Two views of the scale of preferences

There are two useful concepts of a scale of preferences:

- The utilities (satisfactions) are arranged so that the most pressing or urgent requirements are near the top of the scale and those which are just worth satisfying are placed near the bottom. These are the marginal wants, and it is at the margin that changes will be made. The Law of Substitution or Equimarginal Returns will operate: the purchase of goods will be substituted at the margin (some goods will be replaced by others or quantities purchased will be rearranged) so that maximum utilities are preserved. When an individual is spending his money in the optimum way it is yielding Equimarginal returns.

- It is also reasonable to compile a scale of preferences so that every penny spent attracts the same amount of utility. If this were not the case then it would be logical to expect the person to have a different scale of preferences. It is very unlikely that any two people have identical scales of preference. Each person is continually changing the way in which he spends his money, although he would not willingly spend a penny more on one commodity or a penny less on another. As we saw when we studied the method of equilibrium analysis. it is unlikely that maximum satisfaction will be secured even in the short run, so scales of preference are bound to be fluid.

The margin

The margin is the border or frontier of change that is continually influencing the economic system. It is not a fixed line or point, but will advance and recede depending on supply, demand, and price. The economist often finds it convenient to study small units and slight changes in the economic system. We Consumers substitute at the margin as income increases and this applies to consumers in bulk from the macro-economic angle) Gardner Ackley, in Macroeconomic Theory (Macmillan), has stated succinctly that: "Almost without exception budget studies show a relationship between family income and total family consumption like that which Keynes postulated for the total economy."

The marginal unit is the last unit to be added, or the first to be taken away; thus it can be a positive or negative concept The critical concept of the margin is the basis of much economic analysis; we shall find that it is a theme which runs like a recurring refrain through microeconomic studies and, therefore, it will be useful to consider, from the outset, some of the ways in which the term is used

The marginal unit This is the last unit produced or not worth producing, depending on the circumstances prevailing at the time. It is the last unit bought or sold-or not bought and sold as the case may be. It is important to realize that the marginal unit is not necessarily different in quality from any other

Marginal land This lies on the border of change so far as land utilization is concerned. Often marginal land is thought of as infertile land that might be worth cultivating in wartime when agricultural prices are high, but which may be relegated to amused marshland in peacetime. However, infertile land may command a high price for building purposes. Land in urban centres may be marginal in the sense that it might be bought up by a super market chain and be used as a shopping area instead of as a cinema.

The marginal producer He thinks it is just worth while to manufacture a particular article. The marginal producer is by no means the least efficient one. Indeed, the marginal firm may be very adaptable and quick to change to some more profit able line if the opportunity arises. It's difficult in economic studies to examine units small enough to be realistic. The decision to change a particular line of production be a very difficult one A produce of ball-point pen finds it impossible to measure the profitability of producing an extra pen. He may have to consider ten thousand pennies a marginal unit, whereas an airliner is a more distinctive and definable unit.

- Marginal costThis is the cost to the producer of an extra unit or the saving in cost of reducing production by one unit. We shall see later that, if port accepted as a necessary cost of production, then the producer will fix his output at a point where marginal cost and marginal revenue are equal. If the cost of the last unit produced was greater than the revenue received from the sale of it, then the manufacturer would be foolish to produce it. We shall see that his prefix will not be maximized while his marginal revenue is less than his marginal cost.

- The marginal want This is that want just worth satisfying while the marginal purchaser is not promised anything specific in return. chaser to whom the commodity or service is just Although the government is likely to spend its worth the price charged

- Marginal utilityThis is the gain or loss of satisfaction from a slight increase or decrease in the supply of a commodity desired by the purchaser Diminishing marginal utility represents the decreasing satisfaction, which after a certain point, is obtained from each additional unit.

- The marginal rate of substitutionThis involves the substitution at the margin of one commodity for another as the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility comes into effect. Thus, as the stock of one commodity diminishes, a buyer will require larger and larger quantities of another commodity to compensate for sacrificing further units of the first. This could apply to goods in alternative or competitive demand such as tea and coffee.

- The marginal efficiency of capitalA price is different from a tax, because taxpayers revenue largely for the benefit of the citizens, there is difficult concept, defined by Professor Keynes as: "the relation between the prospective yield of one more unit of capital and the cost of producing that unit (General Theory of Employment, Intercell and Moms, Macmillan) The marginal efficiency of capital is the prospective yield on investment and is closely related to the rate of interest.

Price and value

The term price is at the heart of economics therefore we must be certain exactly what we mean by it Price is the exchange value of a commodity or service in terms of money: When a price is paid, () Marginal revenue This is the revenue gained by something definite is expected in return. In order to producer from the sale of a single unit (often secure the use of a commodity, a price will be paid. considered as the last unit produced), total revenue. In order to secure the use of labour, or money, or would be reduced if sales were curtailed by a single business skill, or the hire of goods, a price will be paid The price of labour is the wage, salary, or professional fee. The price of lending money for a period of time is interest. The price of managerial enterprise is profit and the price of hiring land, buildings, cars, or TV sets is rent. (We shall see later that profit and rent are more complex prices) The boundaries of these definitions are arbitrary, for profit will include elements of wages and interest whereas, in modern economic science, rent is considered as the price paid for anything which is in very short supply, including labour, capital or managerial skill.

A price is different from a tax, because taxpayers are not promised anything specific in return. is just Although the government is likely to spend its revenue largely for the benefit of the citizens, there is no promise that the taxes paid for vehicle excise in the licences will be used to improve the roads, or that dog licence money will be spent upon dogs.

The term 'value' is often used as if it were synonymous with price, but value and price are by no means identical. Sir Geoffrey Crowther, in An Outline of Money (Nelson), states that:

The point can be very easily illustrated by supposing that on a given day the price of everything coal, bread, postage stamps, a day's labour, the rent of houses and everything else were to double. Prices would have altered beyond question. But values would not. Value is a relative concept depending on the more subjective idea of one person at a particular time and in a certain place. Exchange-value is objective; use value is subjective. If an individual considers that he has gained a bargain, he means either that be believes the future exchange-value of the article will increase, or the use-value to him is worth more than the exchange-value. A Wembley ticket toot may have bought a number of tickets a few weeks previously thinking that on the day of the match potential spectators would be willing to pay £50 for a ticket If he manages to sell each one at a profit of C10 he has obviously palmed a bargain. Price and value have once more been proved to be different things

Data response 2

(a) Study the following table

| Units of a commodity | Price | Marginal utility |

| First | 10p | 50p |

| Second | 10p | 25p |

| Third | 10p | 12p |

| Fourth | 10p | 8p |

How many units of a commodity will a consumer purchase?

(b) Study the following table which represents a country's production possibilities given two commodities, A and B

| Commodity A | Commodity B |

| 150 | 0 |

| 125 | 50 |

| 100 | 90 |

| 75 | 120 |

| 50 | 140 |

| 25 | 150 |

| 0 | 155 |

if the company is producing 100 units of commodity A and 90 units of commodity B, what would be the

opportunity cost of producing another 30 units of commodity B?

(c) A newspaper costs 20p, & pint of beer 60p and a pound of steak £3 Express the value of each good in

(d) Study the following table

| Commodity | Quantity | Price | Marginal utility |

| A | 5 | 20p | ? |

| B | 10 | 10p | 8 |

Assuming that an individual consumes the quantities of A and B as shown in the table above and is not intending to alter his pattern of consumption, what is the marginal utility (M/U) derived from product A? Use the formula :

M/U of A / Price of A = M/U of B /Price

You Might Also Like

Discover our Economics Homework Blog, an essential repository of expertise and insights. Explore advanced strategies, emerging trends, and innovative approaches to deepen your understanding of fundamental economic principles. Engage with our latest articles to gain fresh perspectives on key topics in economics.